Amazonia can't wait.

The Amazon Regional Observatory is a reference center for scientific knowledge and regional cooperation. While our new website is under development, follow the latest updates from ARO.

Newly released — and essential reading.

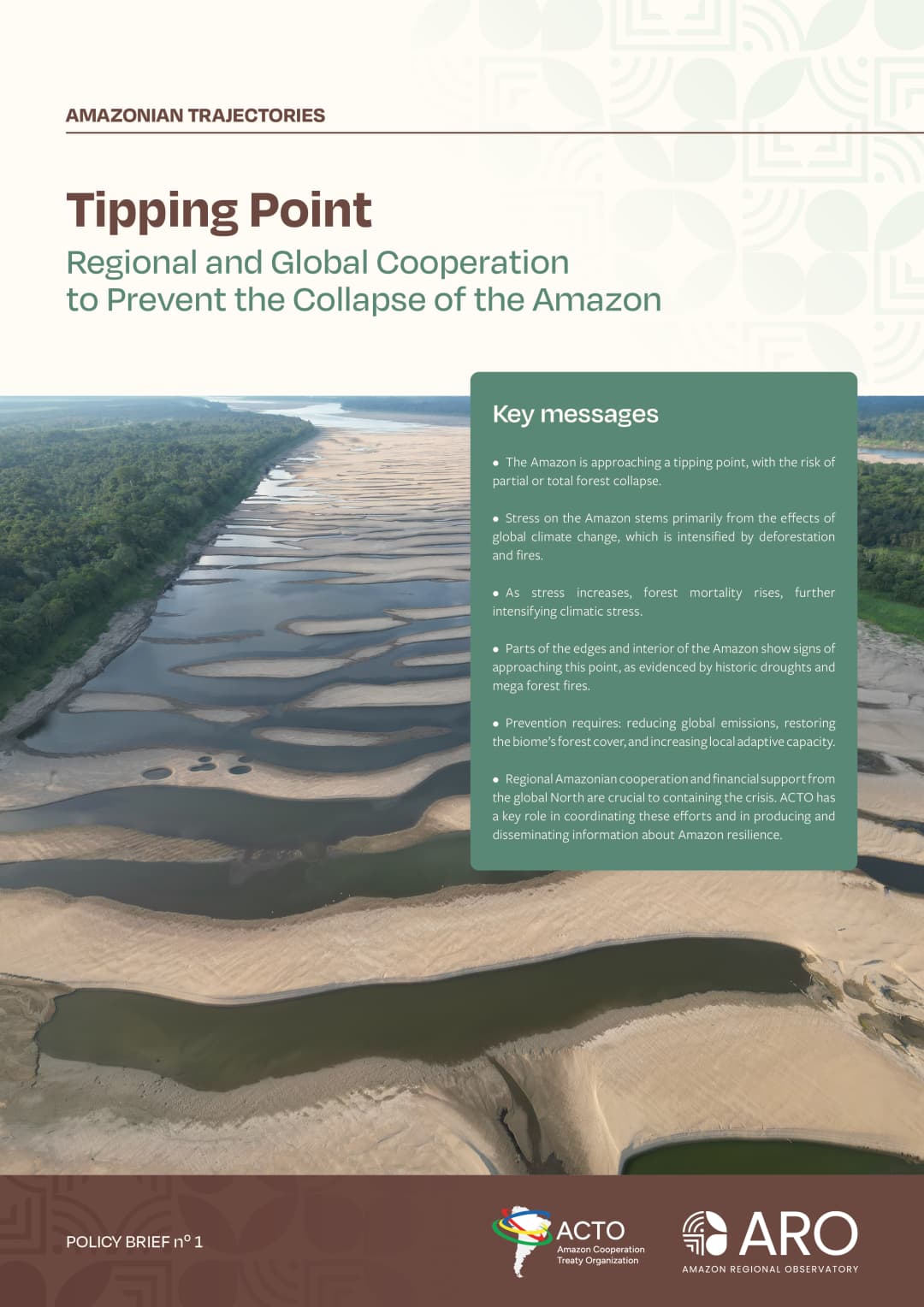

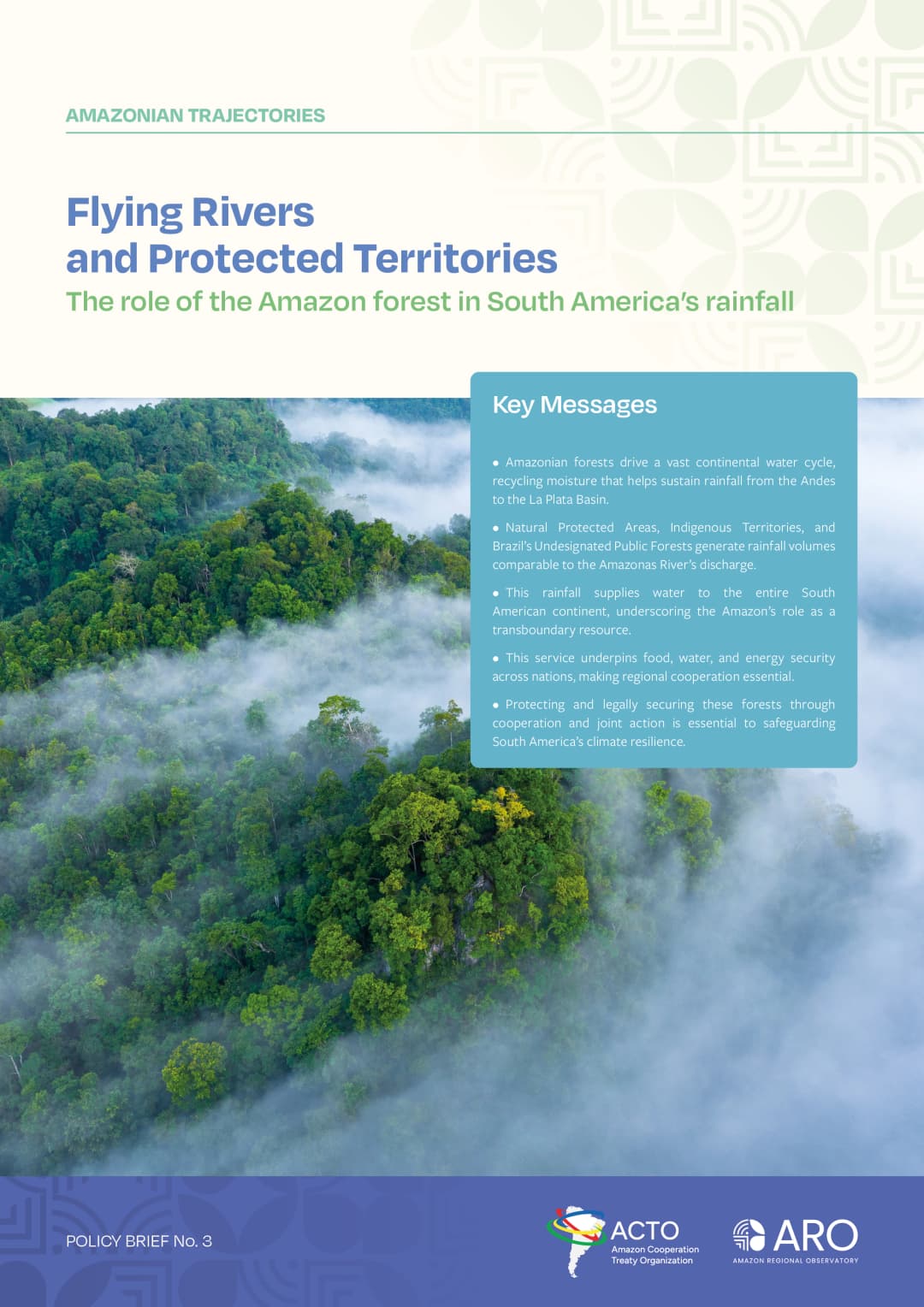

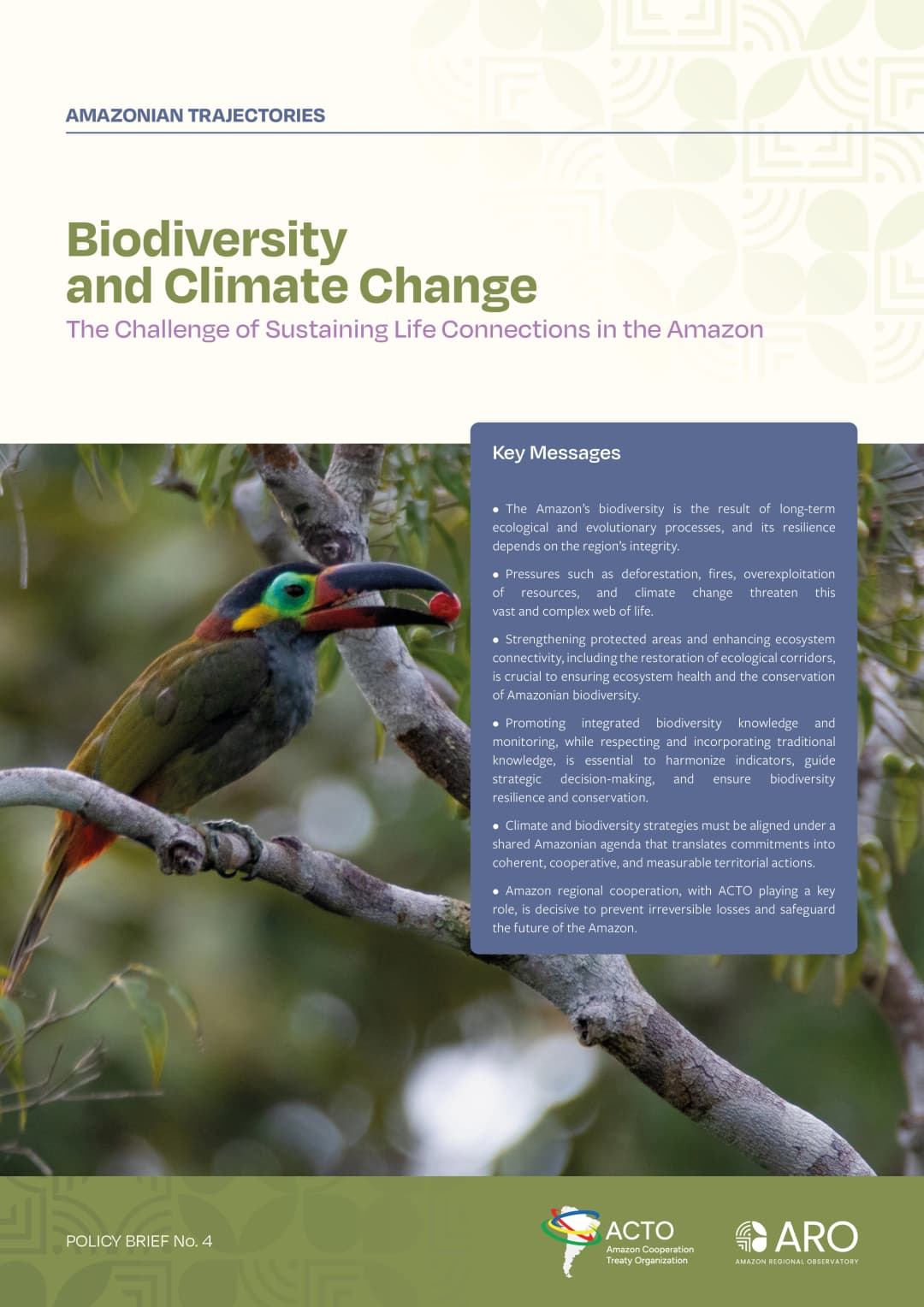

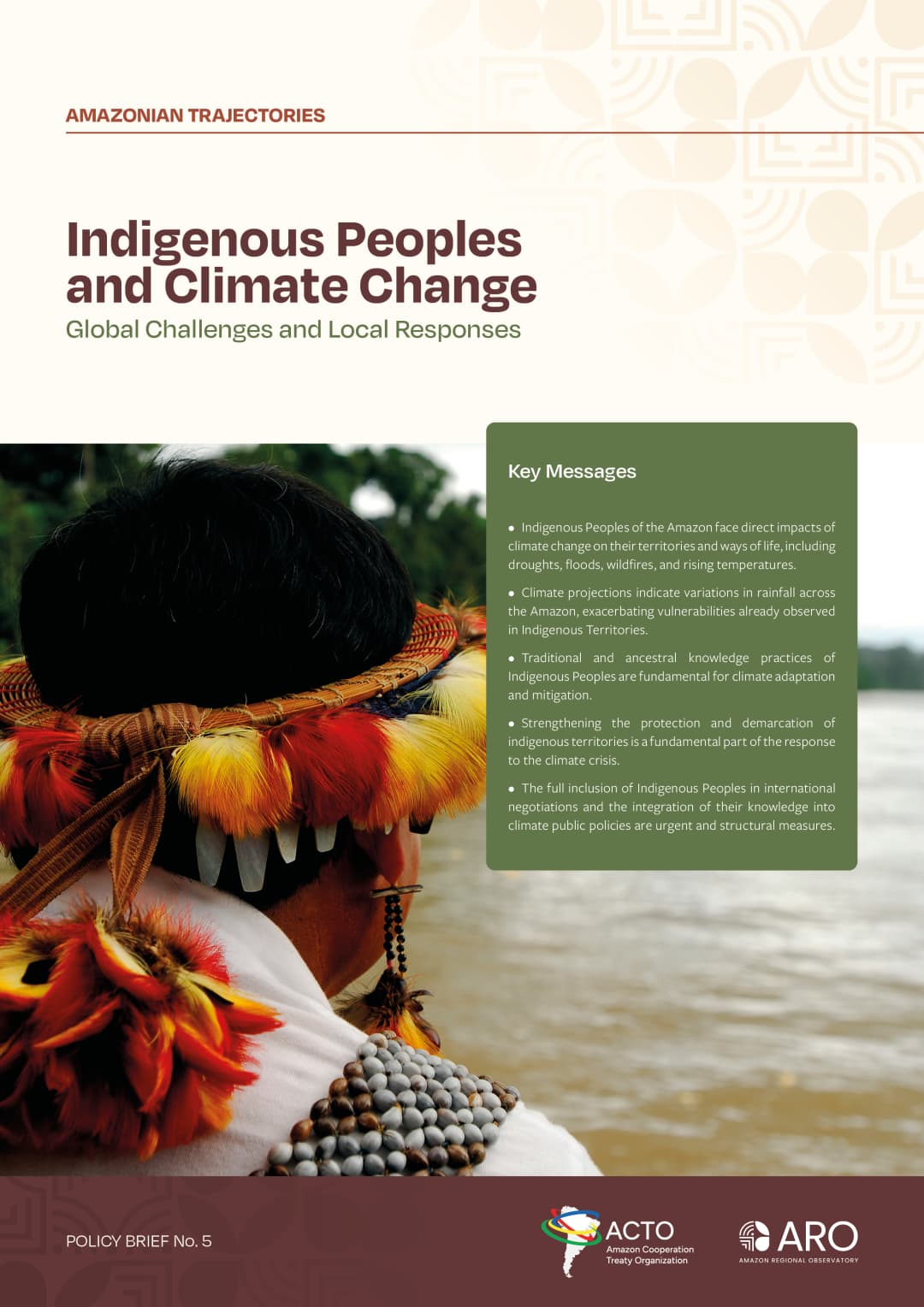

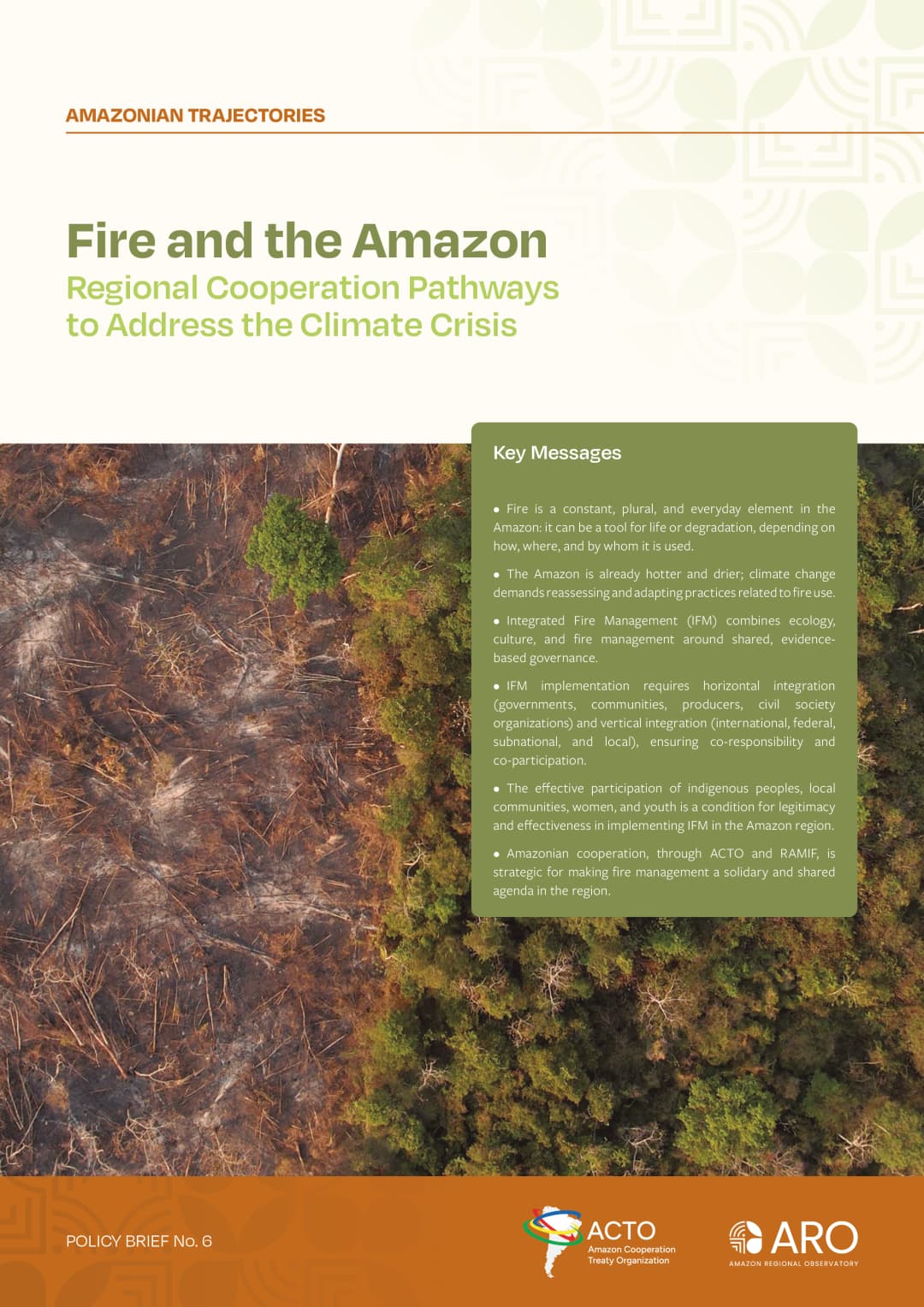

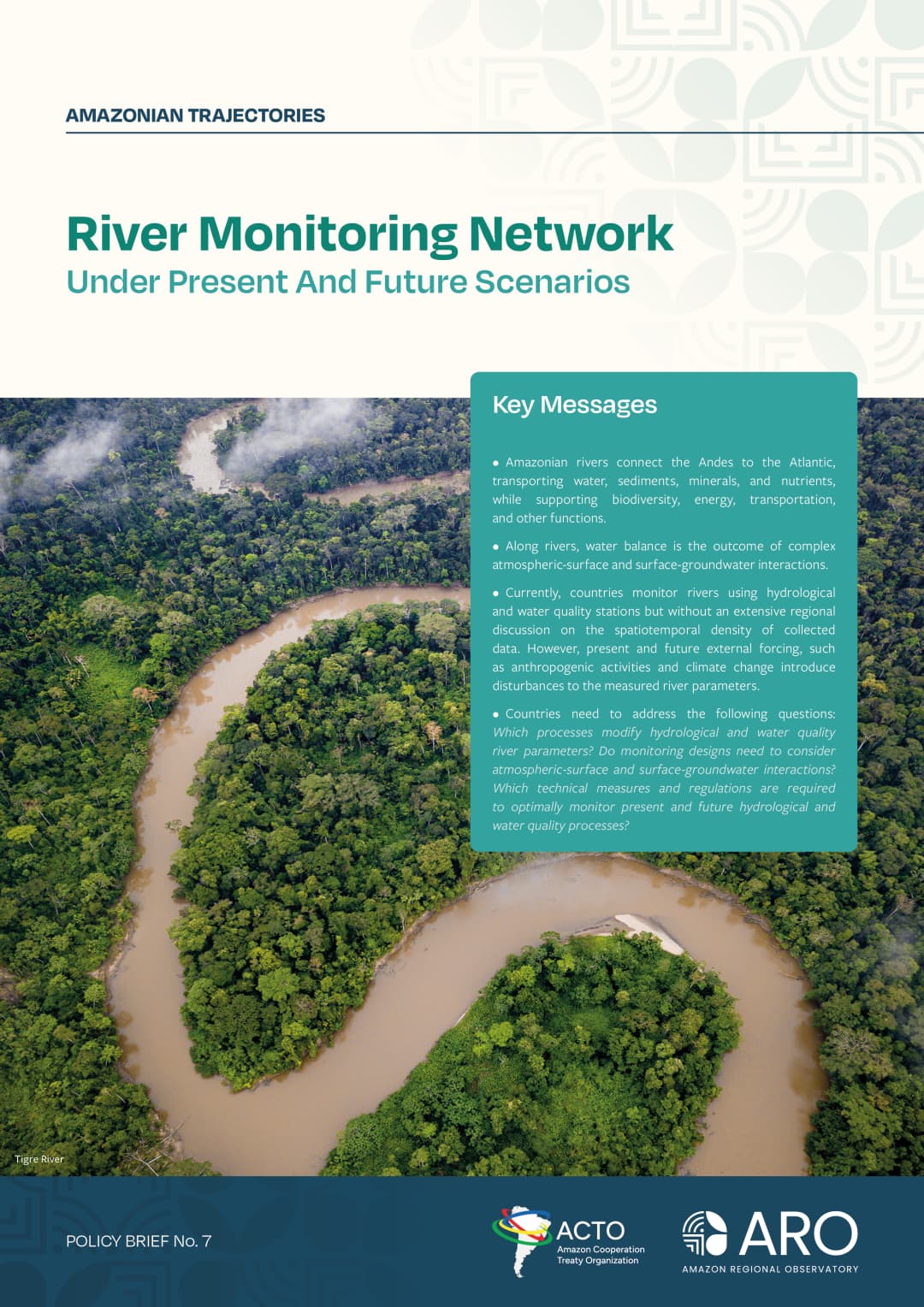

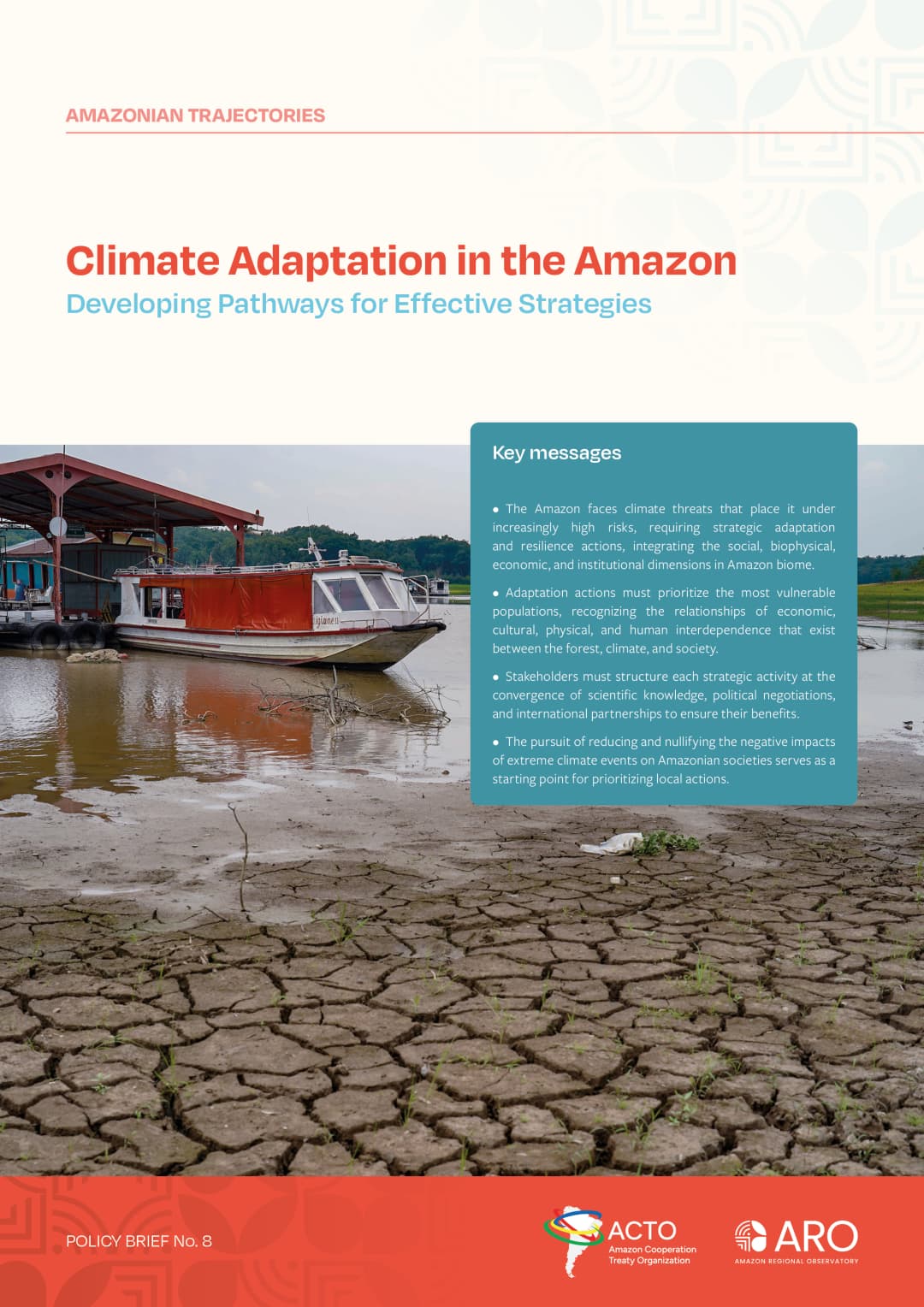

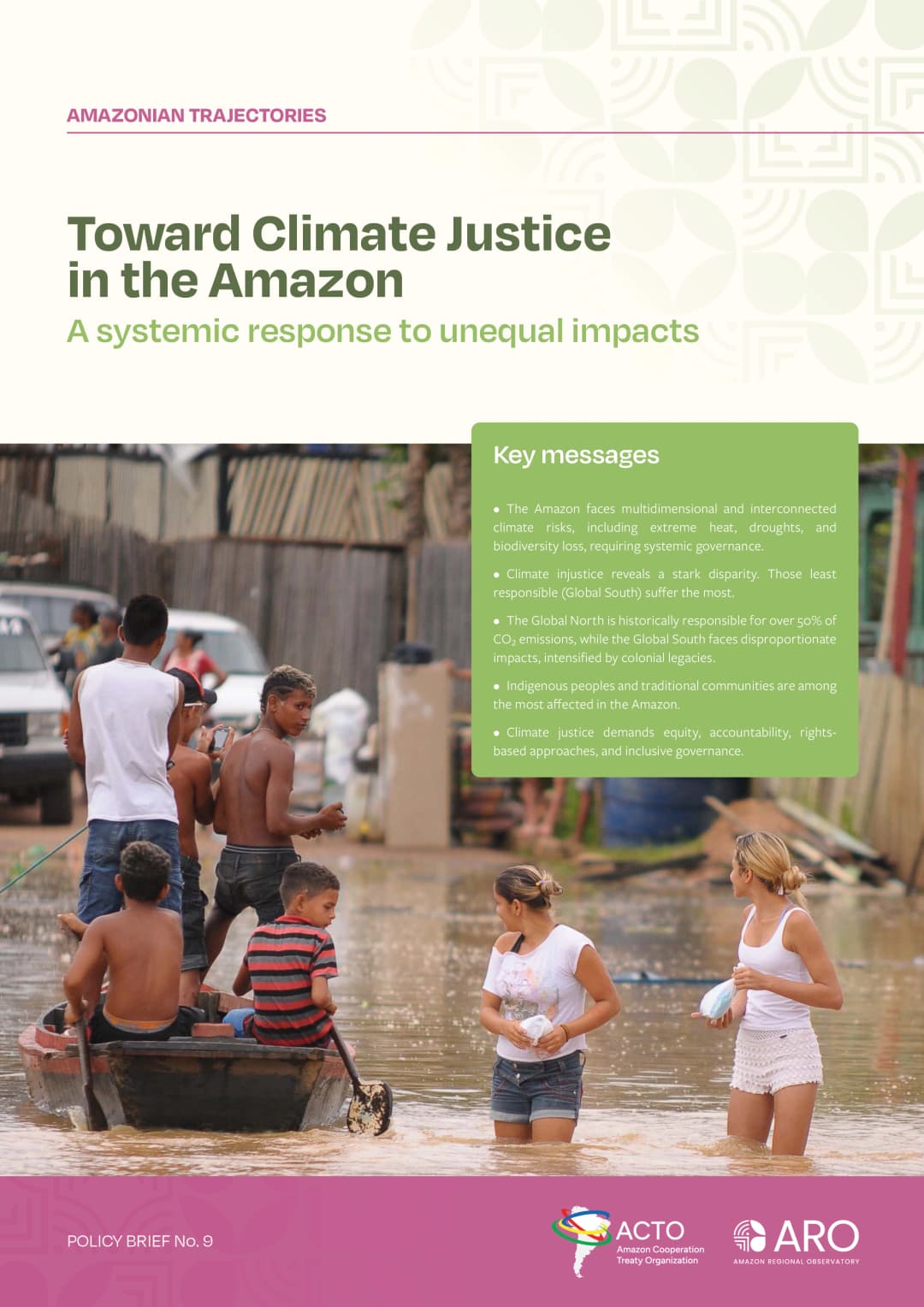

A collection of nine policy briefs produced by ORA's team of experts and consultants, based on current and essential data and research on the Amazon region.

What we are doing now

Explore the latest studies, territorial monitoring, and scientific actions that are shaping the future of the Amazon.

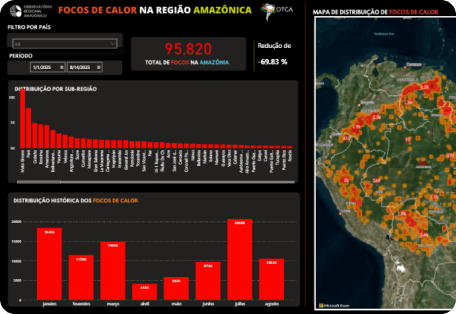

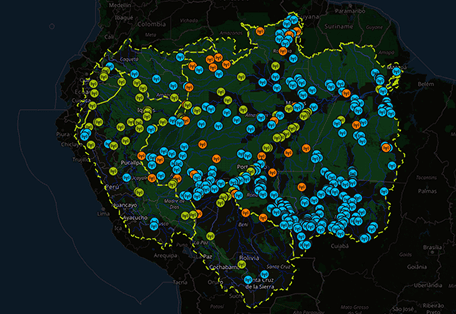

Hydro Amazonia Networks

Monitoring of historical data on hydrology and water quality parameters.

Discover more

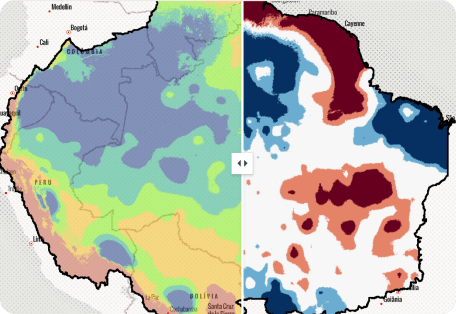

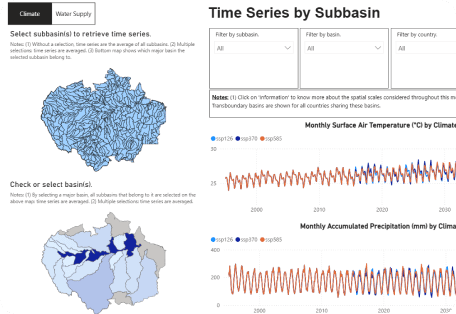

HYDROBID - Water Simulation Model

Hydro platform and multi-sector nexus model for the Amazon basin.

Discover more

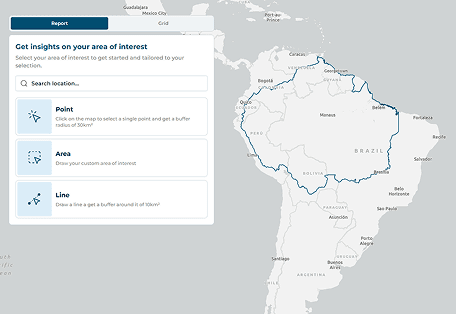

BID - Amazonia Forever 360+

Government reporting tool with data ranging from biodiversity to infrastructure

Discover moreAmazonian Trajectories

Insights from researchers and community leaders shaping the future of the Amazon.

Subscribe to receive updates from the Amazon Regional Observatory.

Stay informed about the latest studies, data visualizations, and strategic actions underway.

Who we are

Amazon Regional Observatory (ARO)

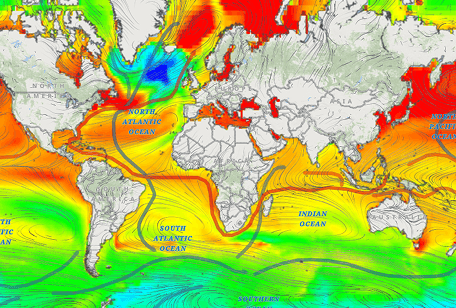

Created in 2021 by the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO), ARO serves as a reference center for essential information on the shared and sustainable management of the Amazon. It brings together national data and provides Amazonian countries with a shared view of the region, supporting cooperation and informed decision-making.

The Observatory monitors critical events that may trigger significant changes in Amazonian ecosystems, helping to identify tipping points. Its role is to integrate, process, and share scientific information collaboratively among governments, research institutions, universities, and civil society.